|

| Arthur Barnett |

Corporal Arthur Barnett, of the Second Battalion, Scots Guards, joined the war in its early days when the fighting was still mobile and relatively fast-moving, when British troops were greeted joyfully by Belgians, and most were hopeful of a quick end to the conflict. Few could envisage what lay store, certainly not Cpl Barnett, who was attached to a Cycle Company. After setting sail from England aboard the SS Minneapolis, this is one of his first entries:

October 6th - 5am We are off the coast of Belgium. We arrive at Zeebrugge at 6am. We disembark at 11am. We are told the supposed position of the enemy. We left Zeebrugge at 3pm, had a ride of about 12 miles to Bruges. We found the Belgium people very nice, they were quite interested in us, we being the first English troops they had seen. A very good road for cycling. Arrived at Bruges 8pm. Quite a reception, everybody wanting buttons for souvenirs. We went through the town of Bruges to the village of Oostcamp [Oostkamp]. We were billeted in a schoolroom, had a good night's sleep.Barnett was part of an advance guard for 7th Division, which was advancing through Belgium, and it wasn't long before he caught his first glimpse of the enemy:

October 11th: Up at 5.30am. We leave for Langerbrugge. One section left to guard the bridge, the rest sent out to search for the enemy. We arrive at Ostacher [Ostakker] no signs of the enemy. I am sent forward with three men, we meet a Belgium Cavalry Patrol who tell us that they have seen the enemy two miles away. We chance our luck to see for ourselves, when we had gone about a mile and a half we saw a patrol of Uhlans [German cavalry], we had a pop at them and retired. There were about 20 of them.

|

| The first page of Arthur's diary |

As his unit advanced, Barnett witnessed Belgian refugees fleeing for their lives, heading for the sanctuary of Britain in their thousands. He also talks of aeroplanes, a very new invention when the Great War began which were used for reconnaissance in the early days. This was a time of rapid technological development, and it wasn't long before fighter planes and bombers were playing their part in the conflict too.

By mid October 1914, the First Battle of Ypres was raging and Cpl Barnett described his part in the fighting:

October 19th: Receive orders to attach ourselves to Head Quarters to act as orderlies. Things are just getting warm now. I see the old Battalion, saw Bert and Hector (the first I have seen them since we left Lyndhurst). About 20 men and Sergt Wilson have been killed. We saw several aeroplanes during the day, English and German. There were hundreds of refugees leaving Baccalare [Becelaere], the Germans having started to bombard the village.

October 20th: Our job was to watch the flanks. We rode [on bicycles] four times the whole length of the firing line. The battle raged all day and all night. We could get no news of casualties. We were sent to Klen-Zillibeke [Klein Zillebeke] to fill a gap. We came in touch with the Uhlans. We advanced too far and came under our own artillery fire, retiring we took up position on the edge of a thick wood, remaining there until we were relieved by the 3rd Cavalry Division.Two days later, Barnett and his comrades had a near escape when they were spotted by a German aeroplane that alerted enemy artillery.

October 22nd: 'We did not have to wait long until were under a very heavy shell fire. Shells to the right, shells to the left, shells in front, and shells behind us, but being in luck's way none in the trenches, they keep up the fun for close on an hour when all at once we are under rifle fire, there was nothing else to do but to rush forward, the enemy believing us to be a strong force retired.'The men pressed on, taking what ground they could, but after the effort of gaining one trench Barnett could write little more than: 'It was now simply hell. We hung on for half an hour. It was awful to hear the moaning of the wounded...the barrel of my rifle was red hot, it burnt my hand.' To make matters worse, Barnett discovered that 'poor old Hector has been killed'.

| |

| Recovering at military hospital, Arthur Barnett stands second left |

Later in the war Arthur Barnett was caught in a mustard gas attack and was shipped home to recover at a military hospital in London. This is where he met his future wife, Violet Spargo. When the conflict ended he had risen to the rank of company sergeant major. When he left the army Arthur earned his living as a detective with London & North Eastern Railway at Kings Cross Station. He died in 1966.

The diary reminds me of another, also covering the early days of war, that I used in my book Letters from the Trenches. Written by a soldier called Sgt George Fairclough, his account is full of colour, drama, and plain speaking and is also well worth a read.

|

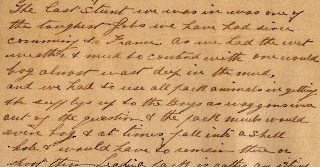

| The final entry of Arthur's diary sums up November 1914 |